Chewing the Heat of Summer

Last Winter, my mother drove us back to her childhood home in Conway, South Carolina; it was the first time I had seen my grandfather in years, and the mood was surprisingly cheerful. We convened on the Hyman’s tobacco farm, comprised of nothing more than soft dirt rows, and the occasional soy bean sprout. It’s nothing like it once was. I remember the bright-star stalks of green tobacco leaves, the yips and screams of slurs that drove through those rows. I remember the first time my grandfather laid his hands on me; it was after my cousin convinced me to grab a hen's egg, and I was only a child. I remember my grandmother’s stories of the domestic violence her husband perpetuated, and I remember the things he told my mother.

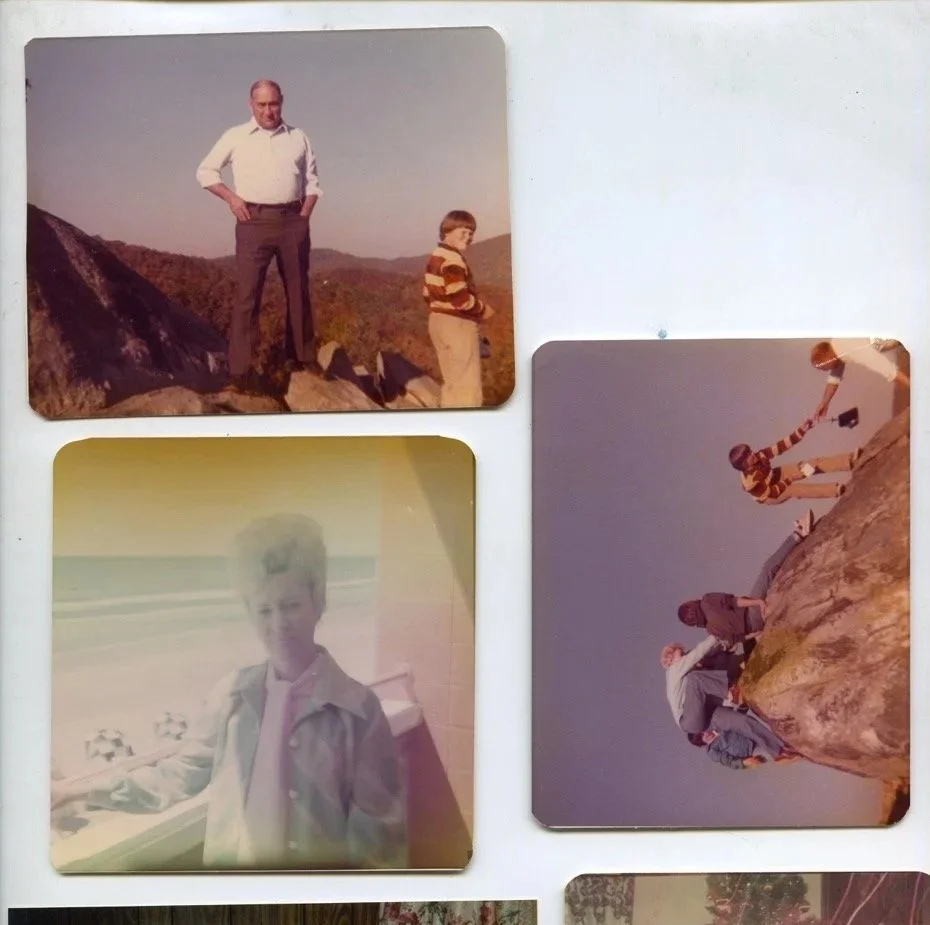

The images presented in Chewing the Heat of Summer directly engage with my own understanding of the American South and the cyclical seeds of hate within agrarian communities, all in conversation with those who cultivate it, my own family.

I owe it to my mother, who denounced it, my grandmother, who escaped it, and I owe it to the little boy I once was: a child who cried underneath that lamplit porch in South Carolina, not understanding what surrounded him, and how he was not so different from it.

But that’s the scariest thing about hate, knowing how easily it could’ve consumed you too.

noun:

1. a doorway, gate, or other entrance, especially a large and imposing one

In bruised color, you wait 3 shots through the (his) Monte Carlo door. where you demand to be let in.

Judy, age 13

to the honorable men who tend dirt roads

Reach down and sweep out dusted hands, scrub off your oiled palms,

though they will always smell of tobacco.

And tonight when you choke your wife, as you always do, the hands that wrap her neck will be much older than your own. After all, the man who tore open her daughter’s blouse with a walnut switch is not that cruel. It’s unbearable musk of tanned leaves that fills her lungs,

choking on the plant that keeps her here. and you there. You’re out of breath and she can no longer hold onto tiled walls,

so wash yourself and forget the acrid prints left on her body; they are not yours to clean.

You’ve had a long night; fresh air may do you some good. Step outside where retching cries cannot be heard past the screen door. Roll a filter and take to your harvest. You deserve it. Look out to the eyes that meet your own, hidden between the gaps of brazen stalks, a windowless spire draped in kerosene.

Throw a cigarette to it, reveal the cross underneath.

Does god call to this land too?

Come morning you will all show up to church, a five-minute drive to the white house where you are greeted like the hero you are; a bible-bound man and his politely quiet family.

The body of christ half-chewed in your mouth,

“forgive me father, it was not I who bled you.”

The wine had already stained your bottom lip.

from what was left

to what’s remained

from whence it came

and back again.

Karen, age 59